[

getting-to-know-memblock.html

]

Getting to know memblock

Less than five seconds – that’s how long you need to wait to get your Linux kernel up and running. But it’s hardly an idle time for Linux – the system has to process configuration, perform architecture-specific setups and initialize many subsystems.

One of such subsystems is memory allocation. In order to prepare it, the kernel needs to have an allocated chunk of memory. But how can we manage memory if we have no memory allocator? We have a chicken and egg situation, but there’s a solution – use a structure that is initialized at build time called memblock. It’s a specialized mechanism that allows Linux to manage memory regions during the early boot phase, before the usual memory allocators are initialized in mm_init().

There are many features offered by memblock:

- Registering physical memory regions

- Marking memory blocks of specific size and alignment as reserved, free or “hidden”

- Allocating a block of memory within the requested range and/or in specific NUMA node

- Controlling allocation direction, memory range and the like

- Checking the memory state, e.g., checking the size of reserved memory or if a particular address exists

Structures

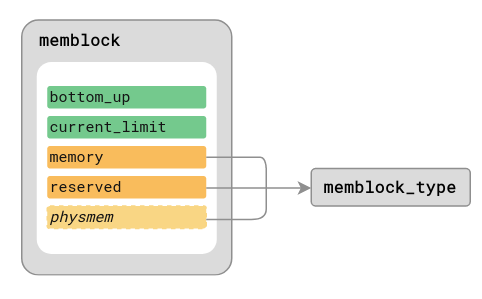

The memory is modelled as a collection of blocks that are either free or allocated. They are stored in the main structure called memblock as two memblock_type members: memory and reserved. It is also possible to define a collection of memory regions that ignores all the flags and shows the whole available physical memory – physmem. This structure is initialized if CONFIG_HAVE_MEMBLOCK_PHYS_MAP flag is defined. It is a pretty small array – it can store only 4 entries. In addition to this, the memblock structure keeps information on the allocation direction bottom_up and physical address of the current memory allocation limit current_limit:

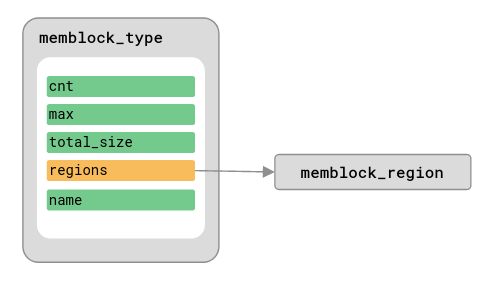

In the memblock world, chunks of memory visible to the kernel are called regions. A collection of memblock_regions is wrapped by the memblock_type structure. regions is a static array that can store 128 entries that can be resized if needed. Other information available in this structure is the combined size of the regions total_size, symbolic name set during initialization name and the number of memory blocks it currently stores cnt:

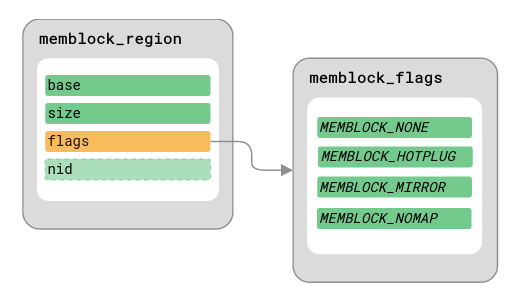

The already mentioned structure, memory_region, is another wrapper that has all the information about memory region – the base physical address base, size of the region size, region attributes flags and, if NUMA nodes are used, a node ID nid:

The region attributes are used to mark if a memory block should be treated in a particular way or not. The available flags are:

MEMBLOCK_NONE– “normal” memory regionMEMBLOCK_HOTPLUG– hotpluggable memory regionMEMBLOCK_MIRROR– mirrored memory regionMEMBLOCK_NOMAP– treat this memory region as it’s reserved, don’t add it to the mapping of the physical memory

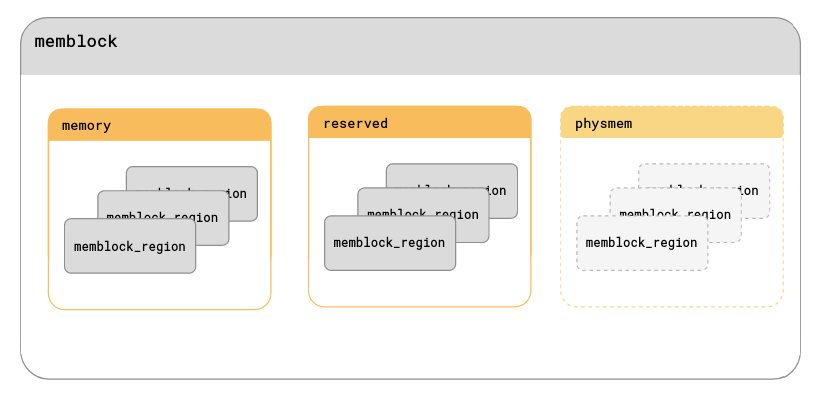

So, the general memblock structure can be visualized like this:

Initialization

Memblock is initialized at the build time as a memblock global variable with the following values:

struct memblock memblock __initdata_memblock = {

.memory.regions = memblock_memory_init_regions,

.memory.cnt = 1, /* empty dummy entry */

.memory.max = INIT_MEMBLOCK_REGIONS,

.memory.name = "memory",

.reserved.regions = memblock_reserved_init_regions,

.reserved.cnt = 1, /* empty dummy entry */

.reserved.max = INIT_MEMBLOCK_RESERVED_REGIONS,

.reserved.name = "reserved",

.bottom_up = false,

.current_limit = MEMBLOCK_ALLOC_ANYWHERE,

};__initdata_memblock is a macro that,

depending on CONFIG_ARCH_KEEP_MEMBLOCK and

CONFIG_MEMORY_HOTPLUG flags, embeds (or

not [1]) the memblock structure in an appropriate data section. As a statically initialized structure,

memblock is available since the very beginning, together with the region arrays, which are initialized as following:

static struct memblock_region memblock_memory_init_regions[INIT_MEMBLOCK_REGIONS] __initdata_memblock;

static struct memblock_region memblock_reserved_init_regions[INIT_MEMBLOCK_RESERVED_REGIONS] __initdata_memblock;The number of available and reserved regions is defined by these macros:

#define INIT_MEMBLOCK_REGIONS 128

#define INIT_PHYSMEM_REGIONS 4

#ifndef INIT_MEMBLOCK_RESERVED_REGIONS

#define INIT_MEMBLOCK_RESERVED_REGIONS INIT_MEMBLOCK_REGIONS

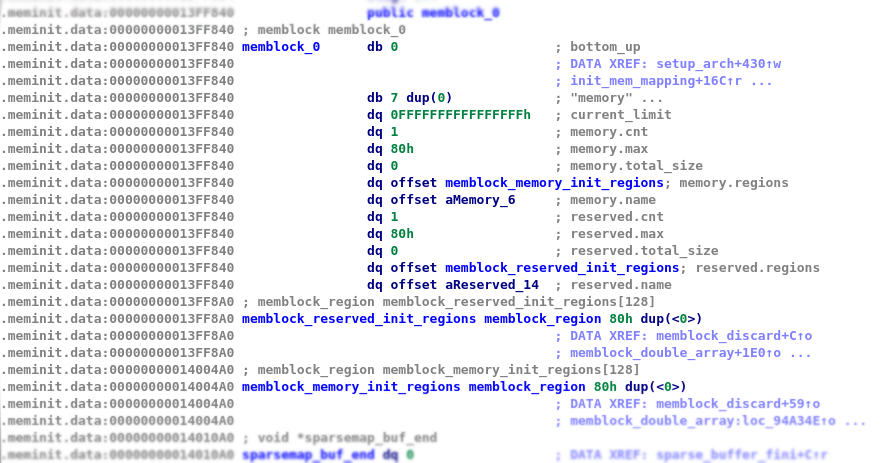

#endifIf we were to take a look at the disassembled Linux image vmlinuz that discards memblock after boot time and has memory hotplugging enabled, we can see an initialized memblock structure in .meminit.data section:

Features

Let’s say you’ve taken a heroic effort to add Linux support for a new architecture, and now you need to implement your own version of setup_arch(). There are many, many things you need to take care of, one of them being memory initialization. You might want to hide some areas of the memory that contain kernel, boot parameters or RAM disk image. Or maybe you wish to allocate some memory for logging purposes.

Whatever action you want to take, memblock can help you with a myriad of functions it offers. We can split them into four groups:

- Basic memory management – a group of functions that allow to mark particular regions as available, reserved or “hidden”

- Memory allocation – functions that allocate memory and can return either physical or virtual addresses

- Helpers – a collection of functions that allow controlling the memblock behaviour like changing limits, trimming memory or checking the state of a memory region

- Internal – low-level functions that are used to iterate over different memory areas, merging adjacent regions of the same type and the like. We won’t talk about them much here

Basic memory management

The basic features of memblock revolve around managing memory regions. Given you have a start address (base) of an area you wish to manage and its size (size), you can: mark it as reserved (or not), register it, so the kernel knows about its existence or simply remove it. The functions that make it possible are:

- memblock_add(base, size) – registers a new region by adding it to

memblock.memoryarray. If the new entry overlaps with any of the already defined, they get merged into one. The corresponding NUMA-specific function ismemblock_add_node(base, size, nid) - memblock_reserve(base, size) – marks a region as allocated by adding it to

memblock.reservedarray. If the new entry overlaps with any of the already defined, they get merged into one - memblock_remove(base, size) – unregisters a region, so it’s hidden from kernel. This function removes an entry for the requested region in

memblock.memoryarray - memblock_free(base, size) – marks a region as no longer in use by removing a corresponding entry in

memblock.reservedarray

Memory allocation

Memory allocation is the core functionality of memblock. It allows you to request a chunk of memory and specify its various parameters: size, alignment, start and end addresses and NUMA node’s ID. The memory allocation functions prioritize granting memory over satisfying the constraints specified by a programmer. For example, if we want to allocate a range of addresses in a specific NUMA node, which is unavailable at the time, memblock will try to allocate memory in a different node within the provided range. If it still doesn’t work, it’ll drop the lower memory limit and return the address to the allocated memory.

There are two kinds of memory allocation functions: such that return physical addresses (memblock_phys_alloc…) and virtual addresses (memblock_alloc...).

Functions returning physical addresses

The first family of functions consists of:

- memblock_phys_alloc(size, align) – allocates a memory block of specified size and alignment

- memblock_phys_alloc_try_nid(size, align, nid) – tries to allocate a memory block on a specified NUMA node. If it’s not available, it allocates memory on any other node

- memblock_phys_alloc_range(size, align, start, end) – allocates a memory block within the requested range of specified size and alignment. Used internally by

memblock_phys_alloc - memblock_alloc_range_nid(size, align, start, end, nid, exact_nid) – allocates a memory block on the requested NUMA node within the specified range. If

exact_nidis false and the node is not available, it can fall back to other nodes to grant memory. If this is not the case, it doesn’t allocate memory and returns 0, signalling failure. It’s a pretty internal function, used outside memblock only in CMA

Note that the memory allocated by these functions is not cleared, and it’s on the programmer to take care of clearing it if needed.

Functions returning virtual addresses

The second group is centred around the memblock_alloc_try_nid function that tries to allocate a block of memory given its size, alignment on a specific NUMA node within the requested range. As it requires a lot of parameters to control, so it’s usually preferred to use one of these functions:

- memblock_alloc(size, align) – allocates a block of memory of a requested size and alignment. The most commonly used function when someone just needs memory and doesn’t care about ranges or NUMA

- memblock_alloc_from(size, align, min_addr) – allocates a memory block of a specific size and alignment above a specified address. If it’s not possible, it’ll drop the lower limit and still allocate memory

- memblock_alloc_low(size, align) – allocates a memory block of a specific size and alignment in the low memory range

- memblock_alloc_node(size, align, nid) – tires to allocate a memory chunk of requested size and alignment in a specific NUMA node. If it’s not available, it allocates memory on any other node

The memory allocated by these methods is cleared and ready to use.

As mentioned before, memblock_alloc_try_nid only tries to meet the criteria,

which means that if it can’t allocate memory in a specified NUMA node, it will find it somewhere else at all costs. If a programmer wishes to force memblock to grant memory only from an exact node, they should use memblock_alloc_exact_nid_raw, which returns NULL on failure. The _raw suffix is used to describe functions that don’t clear memory, similarly to these returning physical addresses.

Helper functions

This is the biggest group that includes functions that change the memblock parameters (e.g., memory limits), query about the memory state, check how much memory is available and many more. Some of the most popular helpers are:

- memblock_phys_mem_size() – a getter function that returns the total size of

memblock.memoryarray. The corresponding helper formemblock.reservedismemblock_reserved_size() - memblock_is_region_memory(base, size) – checks if a region of given base address and size intersects with available memory. Corresponding function checking for an overlap with reserved memory is

memblock_is_region_reserved(base, size) - memblock_set_current_limit(limit) – a setter function that changes

memblock.current_limit, the highest memory address that can be allocated - memblock_allow_resize() – enables resizing of

memblock.memoryandmemblock.reservedarrays, so they can contain more than 128 entries - memblock_end_of_DRAM() – returns the end address of the last available memory region, i.e. the end of memory

For the complete list of helpers, and some internal functions, see memblock.c file, lines 1634 – 1928.

Finale

Once the usual memory allocators are up and running, there’s no much work left for memblock. The last thing it has to do is to release memory to the page allocator. In order to do so, start_kernel calls mm_init, which calls memblock_free_all function down the line. This function traverses the whole memory and frees reserved regions, so they can be used in the “normal” memory allocation.

The memblock structures, like many other boot-time specific structures, stay in the memory until the system initialization finishes. To clean them up, start_kernel calls

arch_call_rest_init, which, among other things, frees the memory occupied by the boot configuration and mentioned structures. Freeing memblock is achieved by

calling memblock_discard function in

page_alloc_init_late.

Still, some architectures, like ARM64 or PowerPC, decide to keep memblock after early boot [2]. To override the default behaviour, they set CONFIG_ARCH_KEEP_MEMBLOCK flag to true, so the memblock_discard call doesn’t do anything and the memblock private memory stays intact.

Summary

Memblock is a mechanism that performs memory management in the early stages of the kernel initialization. The memory here is seen as a collection of regions that are either available to kernel or already allocated. As it could be seen here, memblock gives a lot of flexibility to the programmer. You can manage regions’ visibility to the kernel, reserve memory areas and fine-tune specific parameters like the start/end addresses or even NUMA node’s ID when allocating memory. Thanks to the wealth of functions available, the boot time memory management is convenient and fairly accessible.

Little was said about what’s going on behind the scenes of memblock_alloc functions. That’s something we can look into next time!

References

- Boot time memory management – The Linux Kernel documentation

- 🎥 Boot Time Memory Management, OSS EU 2020

- 🎥 Consolidating representations of the physical memory, LPC 2021

- Memblock implementation – source, header

Credits

The style of diagrams used in this blog post is heavily inspired by the Sourcetrail code visualization tool. I used IDA Free to disassemble the Linux image.

-

[2] – ARM and ARM64 implementations of

pfn_validand PowerPC’skexecrely on representation of the physical memory provided by memblock ⤴