[

memblock-allocs-1.html

]

Unraveling memblock allocs, Part 1

When you take a look at the memblock allocation API for the first time, you might feel a bit overwhelmed. You see a bunch of functions with “memblock_alloc” or “memblock_phys_alloc” prefixes, coupled together with all possible combinations of start/end addresses and NUMA node requirements that you can think of. But this is not a surprising view, given the fact that memblock has to accommodate the needs of ~20 different architectures, from Motorola 68000 through PowerPC to x86 and ARM.

It’s possible to look into the abyss of allocs and understand what are they about. As we will see later on, both groups of

allocation functions, memblock_alloc* and memblock_phys_alloc*[1] use the same logic to find free memory block. Although this

logic is a bit complicated, it makes sense and can be broken down into smaller, easy to digest, parts. After learning the way how

it works, we can apply this knowledge to all functions. We would just need to remember what memory constraints we can ask for

and where.

There’s a lot to take in, so we need to approach this topic with caution. Descending deep down into macros like __for_each_mem_range_rev straight away won’t teach us much about the flow of the allocation process. We have to be able to zoom in and out

when needed. Because of this, I decided to break this analysis down into two parts. In the first one, I’d like to

show you how memblock_alloc* and memblock_phys_alloc* functions converge and discuss the general flow of this

common part. Once we understand how it works, we can move on to the second part. There, we’ll look at the implementation

of the core allocation function and see what it does to grant memory at (almost) all costs. We’ll dissect its internal

parts, delve into details, and get to see quite a lot of helper functions.

Let’s start our analysis with taking a look at two functions -

memblock_alloc and memblock_phys_alloc_range. As you may

recall from the introductory post on memblock[2], the first one represents the

group of functions that return virtual addresses to the allocated memory regions, whereas the second one operates on physical

addresses.

memblock_alloc

One of the most widely used boot time memory allocation functions.

memblock_alloc is used across different architectures to

allocate memory for:

- OS data structures like MMU context managers, PCI controllers and resources

- String literals, like resource names

- Error info logs

- and more

A quick glance at its implementation reveals a quite short function – it’s a wrap for a call

to memblock_alloc_try_nid:

static __always_inline void *memblock_alloc(phys_addr_t size, phys_addr_t align)

{

return memblock_alloc_try_nid(size, align,

MEMBLOCK_LOW_LIMIT, MEMBLOCK_ALLOC_ACCESSIBLE, NUMA_NO_NODE);

}The third and fourth parameter instruct memblock to use the whole address range covered by the entries of the

memblock.memory

array. memblock_alloc

doesn’t care about which NUMA node will be used here. To signal this, NUMA_NO_NODE value is passed in.

Going one step deeper doesn’t reveal much of memblock_alloc

inner workings. memblock_alloc_try_nid is yet another wrapper

that calls memblock_alloc_internal and clears the memory pointed by ptr if one was allocated:

void * __init memblock_alloc_try_nid(

phys_addr_t size, phys_addr_t align,

phys_addr_t min_addr, phys_addr_t max_addr,

int nid)

{

void *ptr;

(...)

ptr = memblock_alloc_internal(size, align,

min_addr, max_addr, nid, false);

if (ptr)

memset(ptr, 0, size);

return ptr;

}Maybe third time’s a charm? Well, memblock_alloc_internal turns out to be yet another wrapper. But it’s a more elaborated one:

static void * __init memblock_alloc_internal(

phys_addr_t size, phys_addr_t align,

phys_addr_t min_addr, phys_addr_t max_addr,

int nid, bool exact_nid)

{

phys_addr_t alloc;

① if (WARN_ON_ONCE(slab_is_available()))

return kzalloc_node(size, GFP_NOWAIT, nid);

② if (max_addr > memblock.current_limit)

max_addr = memblock.current_limit;

alloc = memblock_alloc_range_nid(size, align, min_addr, max_addr, nid, exact_nid);

③ if (!alloc && min_addr)

④ alloc = memblock_alloc_range_nid(size, align, 0, max_addr, nid, exact_nid);

⑤ if (!alloc)

return NULL;

return phys_to_virt(alloc);

}In ①, we check if memblock_alloc and similar wrappers were called when the slab allocator was available[3]. If this is the case, the function uses slab allocation instead of the memblock one and returns.

Moving on, ② checks if the requested maximum address is above the memblock’s memory limit, and caps it if needed. With all of

this from the way,

memblock_alloc_range_nid,

the core allocation function, is called. This function returns the base physical

address of a memory block on success. In the next step ③, memblock_alloc_internal

checks if the allocation was successful. If this wasn’t the case, and we had a minimal address specified

(e.g. was passed via memblock_alloc_from helper), it calls

memblock_alloc_range_nid without the lower address requirement in ④. The check in ⑤ makes sure that we got a valid memory

location before trying to map it to a virtual address (i.e. a void pointer) in phys_to_virt. Given the memblock_alloc_range_nid

call succeeded, memblock_alloc_internal returns a virtual memory address to an allocated memory chunk, returned by

memblock_alloc at the end of the call chain.

memblock_phys_alloc_range

You’ve might have expected to see memblock_phys_alloc

discussed here. Its name contrasts well with memblock_alloc name, the

function itself has a simple signature, and it looks convenient to use. It turns out that it’s the least popular function in

the phys_alloc group. It’s not that interesting anyway, it’s just a wrapper for

memblock_phys_alloc_range:

static __always_inline phys_addr_t memblock_phys_alloc(phys_addr_t size,

phys_addr_t align)

{

return memblock_phys_alloc_range(size, align, 0,

MEMBLOCK_ALLOC_ACCESSIBLE);

}Actually, this one is the most widely used when working with physical addresses. memblock_phys_alloc_range

function is used to allocate memory for:

- Crash kernel logs (1, 2, and more)

- NUMA distance table

- reallocated initrd

As you can see, x86 makes an extensive use of memblock_phys_alloc* functions. Interestingly enough, the word has it that

this family of functions is getting deprecated (source).

Coming back to our function, this is how memblock_phys_alloc_range looks like:

phys_addr_t __init memblock_phys_alloc_range(phys_addr_t size,

phys_addr_t align,

phys_addr_t start,

phys_addr_t end)

{

memblock_dbg(...);

return memblock_alloc_range_nid(size, align, start, end, NUMA_NO_NODE,

false);

}That’s correct, we’ve discovered yet another wrapper. But, wait a second. We saw memblock_alloc_range_nid function before,

didn’t we? Indeed, we saw it just a minute ago in memblock_alloc_internal. This is the common part I’ve mentioned in the

beginning of this post. In fact, the allocation functions that return physical addresses just wrap a call to memblock_alloc_range_nid with specific parameters. Here, we have no preference for NUMA node, and pass the same value as we did

in memblock_alloc.

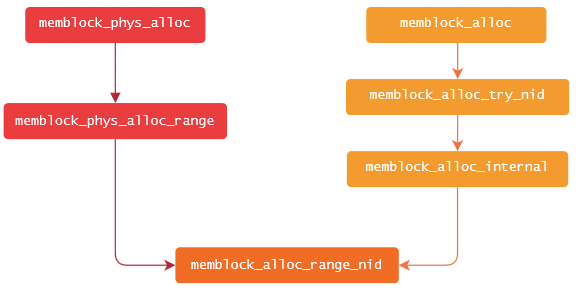

To sum this up in a visual way, the call chains we’ve followed here can be seen this way:

The same pattern emerges for other allocation functions like memblock_phys_alloc_try_nid

or memblock_alloc_low. It turns out that

memblock_alloc_range_nid is called, both directly and indirectly, by a group of functions, where some of them do additional

checks or clean-ups. You don’t need to take my word for it – feel free to take a look at the memblock source code to convince

yourself that this is the case.

The big picture

Now, we can agree that all roads lead to memblock_alloc_range_nid. One more thing you need to know about it is that this

function is very determined to grant memory. It is ready to drop memory requirements passed by the programmer and retry multiple

times to allocate memory before giving up.

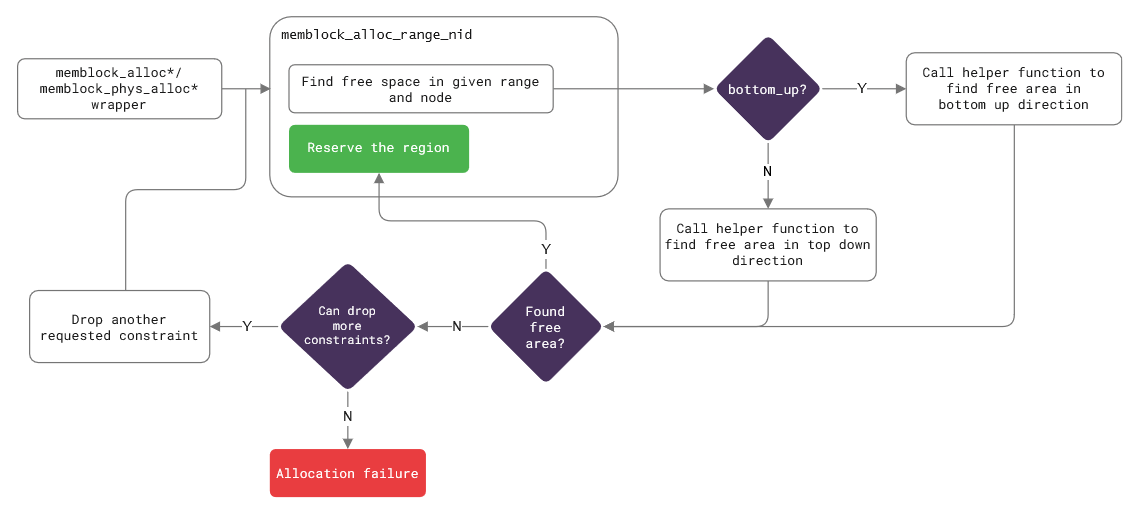

So, what does the general flow of this function look like? In essence, memblock_alloc_range_nid does two things – it first

looks for an available memory region , and then tries to reserve it. Searching for a free memory block is broken down into a

multiple helpers and macros, each of them implemented for both memory allocation directions – top-down and bottom-up. The former

starts allocating from high addresses (that is, from the end of the memory), whereas the latter looks at the low addresses first.

Although bottom up feels more intuitive to think about, most architecture use the top-down direction.

Finding an available memory spot is aided by a low-level helper, which returns the base address of the region on success. If

everything goes well, memblock_alloc_range_nid reserves a region and a new entry in

memblock.reserved is created. If not, the

function checks if it can loosen up the memory requirements, like a preference for a specific NUMA node, and tries to allocate memory

again. This approach works in most cases, so a free region is found and reserved on the next attempt. If we’re out of luck, no

memory gets allocated, and the function returns 0 address to indicate the failure. This process can be pictured as the

following:

What’s next

That’s it for the high-level tour of memblock allocs. Now, you can see how all the functions we thought were doing different

things are actually pretty close to one another. We also discussed the flow of the core allocation function,

memblock_alloc_range_nid, but many questions remain unanswered. What exact memory constraints can be scrapped when memblock

retries allocation? How are memory regions iterated in the top-down direction? Or do we care about memory mirroring at all? To

answer these, we have to take a close look at the implementation of memblock_alloc_range_nid and analyse what bits it uses down

the way. As it’s a lot of work, let’s save it for the part 2 of our investigation.

References

- Memblock implementation – source, header

- 🎥 Boot Time Memory Management, OSS EU 2020

-

[1] - it's a catch-all names for functions in one group, read it as a regular expression ⤴[3] - many architectures free the memblock data structure in

mm_init, which is also where the slab allocator gets initialized. This check is to protect a programmer from using a non-existing, at this point, memblock allocator ⤴